Press Releases

For photos, please click here.

For Tsz Shan Monastery Buddhist Art Museum, please click here.

Clarity‧Compassion‧Action

Tsz Shan Monastery Grand Opening Ceremony cum Inauguration of its Buddhist Art Museum

(27 March 2019) Today the Tsz Shan Monastery announced that its Buddhist Art Museum will welcome visitors with free general admissions to pre-registered visitors from 1 May 2019. Its permanent collection aims to tell the story of Buddhism and how it survives its environment as it moved through the course of history.

Tsz Shan Monastery and its Buddhist Art Museum serve as a centre of Buddhist research and studies for those who seek transcendence and spiritual realisations through Buddha’s teachings of Clarity, Compassion and Action.

The Abbot of Tsz Shan Monastery, Venerable Dr Thong Hong, in his welcoming speech emphasised that the combination of inspiring architectural, historical collection and service programmes in Tsz Shan Monastery created an immersive environment for reflection and for the development of spiritual care and counselling to the community.

Venerable Dr Thong Hong said, “Home is where the Heart is”, which is a fitting analogy of the mission of Tsz Shan Monastery to promulgate the teachings and create benefits for all sentient beings through education, promotion of the arts and services to the community. He also thanked Mr Li Ka-shing for his dedication to the advancement of Buddhist philosophy and his unrelenting resolve inspired many likeminded individuals to further the cause of Tsz Shan Monastery.

Mrs Carrie Lam, Chief Executive of the Hong Kong SAR, said, “Nestled in the grand opus of nature, where tree-lined hills look onto calming seas, the tranquil atmosphere of Tsz Shan Monastery offers the busy world a blissful retreat to put the buzzing world behind and relax its mind. The invaluable collection of Buddhist statues, paintings, carvings and sutras housed in the Tsz Shan Monastery Buddhist Art Museum represent not only the enlightened ideals and cultural sphere of Zen Buddhism but will also provide a base for cultural programmes and activities. The visual and literary culture of the Monastery and its museum will no doubt serve as a quiet space for reflection and the appreciation of Buddhist art for our citizens and visitors.”

Over 2,000 guests gathered to attend the ceremony, amongst whom some 600 are volunteers who have given staunch support to Tsz Shan Monastery. Officiating guests included Abbot Venerable Dr Thong Hong, Hong Kong SAR Chief Executive Mrs Carrie Lam, benefactor of the Monastery and Chairman of Li Ka Shing Foundation Mr Li Ka-shing, Director of Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong SAR Mr Wang Zhimin, Deputy President of The Buddhist Association of China Venerable Ming Sheng, President of The Hong Kong Buddhist Association Venerable Kuan Yun, Chairman of the Board of Tsz Shan Monastery Mr Victor T K Li and Deputy Chairman Mr Richard Li.

In his speech, Mr Li Ka-shing specially thanked those with different values and beliefs for their dedication and support for the mission of Tsz Shan Monastery. He highlighted that the professional ideals they personify was paraphrased in the Eightfold Path – Right View, Right Intention, Right Action, Right Speech, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness and Right Concentration. Such professionalism is the emblematic modus vivendi of Hong Kong and forever the sinew of our Hong Kong story.

Upon his retirement last year, Mr Li adorned a new armour to focus on serving the world through the work of his Foundation. In his speech, Mr Li shared that “No event in my professional life is more important than the decision to set up my foundation, to have the opportunity to serve the future and the betterment of the world side by side is a true blessing.”

Quoting his favorite Dharma teachings in the Diamond Sutra that posit all phenomena are like a dream, an illusion, a bubble, a phantom, Mr Li believes that grasping the world beyond the immediate happenings of daily life is an art and we all need to find answers to the bold and hard questions “Who am I? What should I do with my life?” and most importantly “In what direction should we move forward and thrive together?” The future, whatever it might be – is defined by our purposeful trajectory of wisdom, compassion and undertakings. He hopes Tsz Shan Monastery can be a space for such quiet contemplation and orientations.

The fund for land acquisition, planning and construction of Tsz Shan Monastery and Buddhist Art Museum, and the endowment for operation costs are all donated by The Li Ka Shing Foundation. To date, cumulated total has reached HK$3 billion.

The initiation for Tsz Shan Monastery?

We all have a precious mani pearl deep in our minds, long obscured by dust and toil; now when the dust is gone and its light shines forth, a myriad of illuminations blossom across our mountains and rivers. This illumination will inspire us and we, in turn, will be an inspiration to the world. He is committed to establishing a Buddhist temple and an institute of Buddhist studies to advance the understanding of Buddha’s wisdom, philosophy and teachings. Since its opening in 2015, the monastery has welcomed near one million visits.

How did Mr Li come up with the idea of building a Buddhist Art Museum?

Mr Li Ka-shing believes that Buddhism is a philosophy for everyone, and the Museum in Tsz Shan Monastery aims to tell the story of Buddhism and how it survives its environment as it moves through the course of history. Many of the exhibits housed show the beautiful transcendence smile of the Buddha, yet behind this smile is the story of human dedication and suffering. The Museum aims to embody and express the life and teachings of Buddhism through its collection, and enriches those who seek transcendence and spiritual realisations with an opportunity to explore beyond the symbolism and the art for the essence of the Buddhism.

It took three years to plan and build the Museum, but since the start of its construction more than 10 years ago, Mr Li also developed the idea of building an art museum to promulgate Buddha’s teachings.

What is the area of the Buddhist Art Museum? How big is its collection?

The base area of the Guan Yi statute is 24,000 square feet, comprising the Museum and activity rooms for talks and Buddhist education. The Museum houses 100 Buddha statues, with 43 hand-copied Dun Huang Sutra exhibited by rotation. The Buddhist relics are either donated by Mr Li personally to the Foundation, or directly acquired by the Foundation. They will be kept permanently for exhibition in the Museum and open to the public for free visits.

How did Mr Li select the collection?

Tsz Shan Monastery formed a selection committee of local and foreign experts in Buddhist culture to advise Mr Li in selecting the exhibits. The relics selected feature the three major Buddhist traditions (Chinese Han Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism) and its installations explore and inform how Buddhism integrates and with different cultures.

###

Photo captions

(Download)

1. Speaking at the Tsz Shan Monastery Grand Opening Ceremony, LKSF Chairman Mr Li Ka-shing specially thanks those with different values and beliefs for their dedication and support for the mission of Tsz Shan Monastery.

1. Speaking at the Tsz Shan Monastery Grand Opening Ceremony, LKSF Chairman Mr Li Ka-shing specially thanks those with different values and beliefs for their dedication and support for the mission of Tsz Shan Monastery.

(Download)

2. Hong Kong SAR Chief Executive Mrs Carrie Lam, LKSF Chairman Mr Li Ka-shing (fourth from right), Director of Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong SAR Mr Wang Zhimin (third from right), Chairman of the Board of Tsz Shan Monastery Mr Victor T K Li (third from left), Tsz Shan Monastery Abbot Venerable Dr Thong Hong (second from right), Deputy President of The Buddhist Association of China Venerable Ming Sheng (second from left), President of The Hong Kong Buddhist Association Venerable Kuan Yun (first from right), and Deputy Chairman of the Board of Tsz Shan Monastery Mr Richard Li officiate at the Grand Opening Ceremony of Tsz Shan Monastery.

2. Hong Kong SAR Chief Executive Mrs Carrie Lam, LKSF Chairman Mr Li Ka-shing (fourth from right), Director of Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong SAR Mr Wang Zhimin (third from right), Chairman of the Board of Tsz Shan Monastery Mr Victor T K Li (third from left), Tsz Shan Monastery Abbot Venerable Dr Thong Hong (second from right), Deputy President of The Buddhist Association of China Venerable Ming Sheng (second from left), President of The Hong Kong Buddhist Association Venerable Kuan Yun (first from right), and Deputy Chairman of the Board of Tsz Shan Monastery Mr Richard Li officiate at the Grand Opening Ceremony of Tsz Shan Monastery.

(Download)

3. LKSF Chairman Mr Li Ka-shing dots the eyes of the dragon to celebrate the Grand Opening Ceremony of Tsz Shan Monastery.

3. LKSF Chairman Mr Li Ka-shing dots the eyes of the dragon to celebrate the Grand Opening Ceremony of Tsz Shan Monastery.

(Download)

4. Hong Kong SAR Chief Executive Mrs Carrie Lam, LKSF Chairman Mr Li Ka-shing (fourth from right), Director of Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong SAR Mr Wang Zhimin (third from right), Chairman of the Board of Tsz Shan Monastery Mr Victor T K Li (third from left), Tsz Shan Monastery Abbot Venerable Dr Thong Hong (second from right), Deputy President of The Buddhist Association of China Venerable Ming Sheng (second from left), President of The Hong Kong Buddhist Association Venerable Kuan Yun (first from right), and Deputy Chairman of the Board of Tsz Shan Monastery Mr Richard Li officiate at the inauguration of Tsz Shan Monastery Buddhist Art Museum.

4. Hong Kong SAR Chief Executive Mrs Carrie Lam, LKSF Chairman Mr Li Ka-shing (fourth from right), Director of Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong SAR Mr Wang Zhimin (third from right), Chairman of the Board of Tsz Shan Monastery Mr Victor T K Li (third from left), Tsz Shan Monastery Abbot Venerable Dr Thong Hong (second from right), Deputy President of The Buddhist Association of China Venerable Ming Sheng (second from left), President of The Hong Kong Buddhist Association Venerable Kuan Yun (first from right), and Deputy Chairman of the Board of Tsz Shan Monastery Mr Richard Li officiate at the inauguration of Tsz Shan Monastery Buddhist Art Museum.

(Download)

5. Chief Executive Mrs Carrie Lam and Director of Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong SAR Mr Wang Zhimin appreciate the Ancient Manuscripts in the museum with Mr Li Ka-shing.

5. Chief Executive Mrs Carrie Lam and Director of Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong SAR Mr Wang Zhimin appreciate the Ancient Manuscripts in the museum with Mr Li Ka-shing.

(Download)

6. Chief Executive Mrs Carrie Lam and Director of Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong SAR Mr Wang Zhimin (second from left) take a group photo with Mr Li Ka-shing, Mr Victor T K Li (first from left) and Mr Richard Li (first from right) in front of the Guan Yin Statue.

6. Chief Executive Mrs Carrie Lam and Director of Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong SAR Mr Wang Zhimin (second from left) take a group photo with Mr Li Ka-shing, Mr Victor T K Li (first from left) and Mr Richard Li (first from right) in front of the Guan Yin Statue.

(Download)

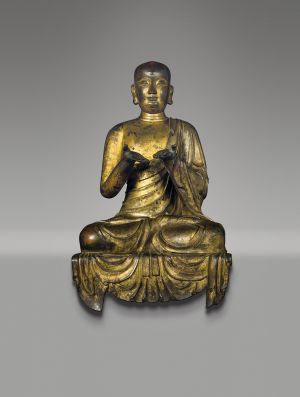

Gilt bronze seated Luohan – China Ming dynasty in the first half of the 15th century. In Mahāyāna texts, before Śākyamuni entered parinirvāṇa, he requested 16 Great Luohans not to enter parinirvāṇa, but remain in the mortal world as Dharma protectors (Dharmapālas). The statue is stylistically similar to the statuary produced or commissioned by the Ming court during the Yongle reign (1403-1424) and Xuande reign (1426-1435). Although no Luohan statue of the Yongle and Xuande reigns has been found so far, the impressive size and superb modelling technique demonstrated by this statue strongly suggest that it is closely related to the imperial atelier of the early Ming dynasty.

Gilt bronze seated Luohan – China Ming dynasty in the first half of the 15th century. In Mahāyāna texts, before Śākyamuni entered parinirvāṇa, he requested 16 Great Luohans not to enter parinirvāṇa, but remain in the mortal world as Dharma protectors (Dharmapālas). The statue is stylistically similar to the statuary produced or commissioned by the Ming court during the Yongle reign (1403-1424) and Xuande reign (1426-1435). Although no Luohan statue of the Yongle and Xuande reigns has been found so far, the impressive size and superb modelling technique demonstrated by this statue strongly suggest that it is closely related to the imperial atelier of the early Ming dynasty.

(Download)

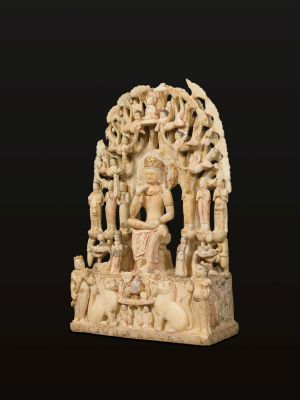

Pensive Bodhisattva – China Northern Qi dynasty (550-577 CE). This openwork niche carved from white stone is noted for its complex composition, rich layering, meticulous carving, extraordinary height exceeding 60 cm, and the vibrant pigments still surviving on the stone surface. It is an extreme rarity among white stone sculptures of the Northern Qi dynasty.

(Download)

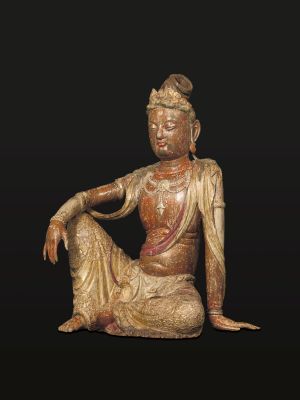

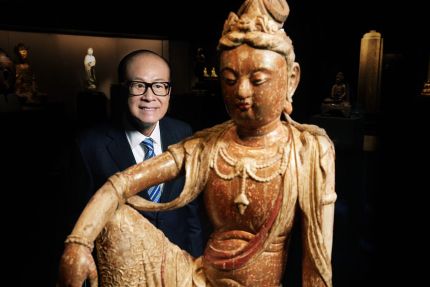

Seated Guanyin Bodhisattva – China Liao dynasty (916-1125 CE). The iconography of Bodhisattva Guanyin varies tremendously. The one portraying Guanyin sitting leisurely with one hand resting on the rocky seat, while another hand placing on the knee of his bent leg was created during the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) in the eighth century. According to the Avataṃsakasūtra, this was an important iconography in China from the 11th to the 13th century, commonly seen among Buddhist statuary of the Song (960-1279 CE), Liao (916-1125) and Jin (1115- 1234) dynasties. The long skirt around the lower body of the statue has undergone restoration during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). The gelled appliqué cloud motifs highlighted with colloidal gold painting around the knees and bordering the hems are Ming additions.

(Download)

Standing Kṣitigarbha, Bodhisattva – Japan Kamakura period (1192-1333). The Kṣitigarbha vowed not to achieve Buddhahood until all hells are emptied, thus, he is also venerated as the Lord of Hell. He is also an extremely important Bodhisattva with profound influence on Chinese and Japanese Buddhism. This Kṣitigarbha statue has a monk image. The six rings at the top of the metal staff carried in his right hand symbolise all beings in the Six Realms of Existence. The raised left hand holds a wish-fulfilling jewel (cintāmaṇi). According to Buddhist text, he “holds the wish-fulfilling jewels in his two hands” and “fulfils wishes as the wish-fulfilling jewel does.”

(Download)

Standing Śākyamuni Buddha – Gandhāra Kushan dynasty second to third century CE. Gandhāra, one of the 16 kingdoms of ancient India, was located in the northwestern part of the subcontinent a round present-day Peshawar Valley in northern Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan. Since it had been under Hellenistic rule, its art was stylistically deeply influenced by Greco-Roman art. Although the statue is partially damaged, the realistic style of Gandhāran sculptures is still well-demonstrated.

(Download)

Seated Buddha Protected by the Nāga King – Cambodia Khmer Empire 12th to 13th century. When the Buddha was in deep meditation under the Bodhi Tree in Bodh Gaya, a violent storm broke out and continued for seven days. On seeing this and fearing that the Buddha might get hurt, Mucilinda the Nāga King left his abode and wrapped seven coils around the meditator. He also transformed his serpent head into multiple hoods and spread them above the Buddha’s head to protect him. The primary role of the Buddha carved in the round and the supportive role of the Nāga King rendered in bas-relief are harmoniously represented.

(Download)

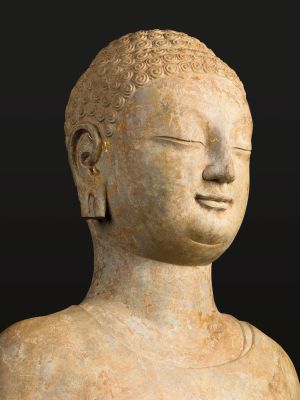

Bust of Buddha – China Northern Qi dynasty (550-577 CE). Buddhist sculptures known as Qingzhou Statuary are mainly distributed in the northern part of Shandong Province. Noted for their unique style and superb artistic value, these statues demonstrate one of the important regional styles in the late period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-589 CE). Qingzhou Statuary are known for their strong regional flavour. The well-rounded face is delicately featured with plump cheeks, a broad smooth forehead, long narrow eyes, full lips with deeply indented and uplifted outer corners, and a placid and kindly countenance. The diaphanous and close-fit kāṣāya, covering both shoulders, is devoid of drapery depiction. All these contribute to the aesthetic uniqueness of Qingzhou Statuary.

(Download)

Head of Buddha with Regal Crown – China Ming dynasty 15th century. A Buddha normally wears no crown and strings of jewellery. However, this head with a tall crown also has tight snail-like conical curls and other characteristic features of a Buddha, indicating that the head originally belonged to a Buddha statue. The tall openwork crown above the Buddha’s head is elaborately and exquisitely constructed with continuous beads, flowers and beaded floral motifs. The Buddha’s facial features and the crown’s style share similarities with several seated Buddhas inside the Grand Hall of Guangsheng Monastery in Hongtong County, Shanxi Province. The statues were carved during the Jingtai reign (1450-1456) during the Ming dynasty. This Buddha head is believed to have been produced in Shanxi in the mid-Ming dynasty.

(Download)

Seated Amitābha Buddha – China first year of the Chuigong reign (685 CE) Tang dynasty. Amitābha (Buddha of Infinite Light), also known as Amitāyus (Buddha of Infinite Life), is the Lord of the Western Pure Land. Since Monk Shandao (613-681 CE) of the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) advocated the chanting of Amitābha’s name to achieve salvation, the Pure Land belief associated with Amitābha began to prevail, laying the foundation for the development of the Pure Land School during the Tang dynasty. According to the votive inscription engraved on the front edge of the base, this Amitābha statue was presented by a donor in honour of his deceased parents.

(Download)

Guanyin Bodhisattva Seated on Lion Mount – China Ming dynasty 15th century. This majestically modelled and meticulously crafted statue attests to the incorporation of even more Chinese characteristic elements into the style of early Ming (1368-1644) imperial Buddhist statuary. It is a brilliant masterpiece of sculptural art of the late 15th century.

(Download)

Standing Śākyamuni Buddha from Gandhāra Kushan dynasty second to third century CE bears strong flavour of western art, casting profound influence on early Chinese Buddhist statuary.

(Download)

Gilt bronze seated Luohan, from China Ming dynasty in the first half of the 15th century, has a youthful and handsome countenance. Luohans were disciples of Śākyamuni, who apart from being practitioners, were associated with guarding the Buddhist Dharma, edifying sentient beings, and removing perils.

(Download)

This delicately featured bust of Buddha from China Northern Qi dynasty (550-577) is one of Mr Li’s favourite pieces of the collection.

This delicately featured bust of Buddha from China Northern Qi dynasty (550-577) is one of Mr Li’s favourite pieces of the collection.

(Download)

Seated Guanyin Bodhisattva from China Liao dynasty (916-1125 CE) portrays a Bodhisattva sitting leisurely, exuding the inner peace needed to practice Buddhism.

(Download)

Head of Buddha with exquisitely constructed Regal Crown from Ming dynasty (1368-1644), shares similarities in style with other Buddha statues produced in Shanxi Province, reflecting Buddhism’s place in a diverse world.

(Download)

Pensive Bodhisattva from China Northern Qi dynasty (550-577 CE) is noted for its complex composition, rich layering, and meticulous carving. The left foot is stepping on a lotus platform, denoting the Bodhisattva’s empathy with human suffering.

(Download)

Seated Buddha Protected by the Nāga King from Cambodia Khmer Empire 12th to 13th century. The Buddha was in deep meditation under the Bodhi Tree wheb a violent storm broke out. Mucilinda the Nāga King left his abode to protect him.

(Download)

Standing Kṣitigarbha Bodhisattva from Japan Kamakura period (1192-1333) holds a wish-fulfilling jewel (cintāmaṇi) in his raised left hand. Mr Li considers the Kṣitigarbha, who vowed not to achieve Buddhahood until all hells are emptied, as a true “action hero”.

Links

Video footage of the Buddhist statues in the Museum:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-zh9qrqrIR8&feature=youtu.be

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1iPasDoiec69zuEO3huG3k0N8YAKikyni/view

About the Li Ka Shing Foundation

The Li Ka Shing Foundation was established in 1980 to work on education, medical services and research initiatives. To date, Mr Li has invested over HK$25 billion across 27 countries and regions, with about 80% of the projects within the Greater China region. In 2006, Mr Li described his philanthropic effort as akin to having another son in the family. He called for a paradigm shift in our Asian culture of giving, through apportioning more of our wealth and means towards social capital so that we could bring forth great hope and promises for the future.

For enquiries, please contact:

Link-work Communications (HK) Ltd

Ms Kat Chan

Tel: (852) 2918-0904

Email:kat.chan@link-work.com.hk

Mr Ricky Lai

Tel:(852) 2918-0905

Email: ricky.lai@link-work.com.hk